i NEWS PAKISTAN

Chapter V: Pakistan’s Debt Situation

“Home life ceases to be free and beautiful as soon as it is founded on borrowing and debt”.

Henrik Isben

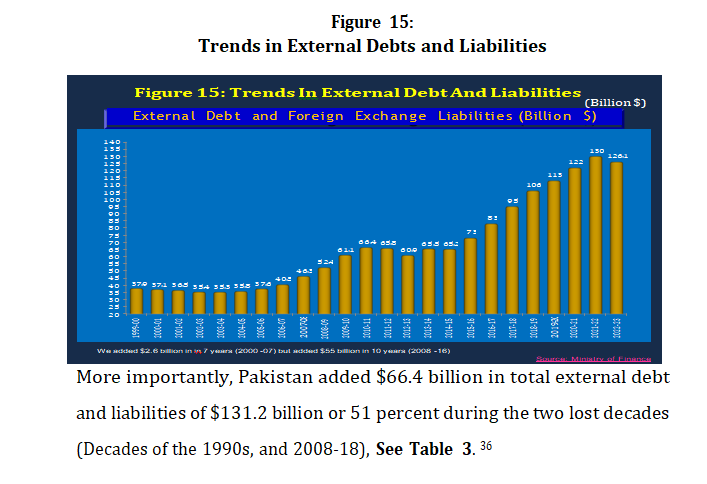

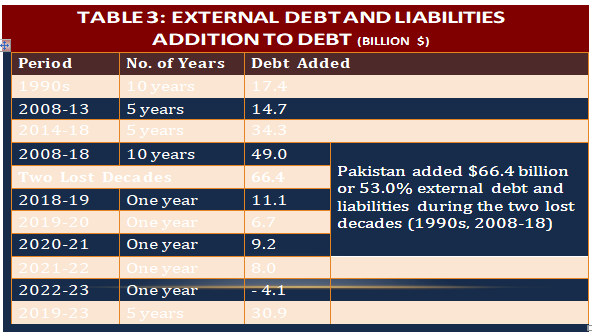

Pakistan’s current debt situation is far worse than many of the LICs and hence it deserves to receive debt relief urgently. Pakistan’s debt situation has been worsening since 2008 but has deteriorated at a speed never witnessed before since 2019. Pakistan’s external debt and liabilities have been growing at differing pace since 2000. They grew at an average rate of 1.4 percent per annum during 2000-2007; the pace accelerated to 6.2 percent per annum during 2008-2015; the pace further accelerated to 8.6 percent per annum during 2016-2023. By end- December 2023, Pakistan’s external debt and liabilities stood at $131.4 billion – rising from $36.5 billion in 2000. In other words, Pakistan added almost $95 billion external debt and liabilities in just 23 years as against $37.1 billion in the last 53 years prior to the year 2000, that is, since independence in 1947 (See Figure 15).

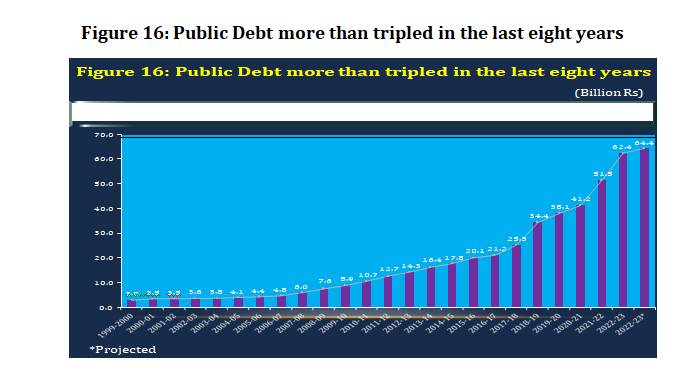

Public debt, on the other hand, is influenced by the size of the budget deficit, rate of depreciation of the currency and interest rate. Like external debt and liabilities, the rise in public debt exhibited different pace since the year 2000. Public debt grew at an average rate of 8.0 percent per annum during 2000-2007; accelerated at the rate of

16.5 percent per annum during 2008-18; and grew at a dangerously high level of 21.3 percent per annum during 2019-2023. Devaluation of Pakistani currency and the persistence of unprecedentedly high interest have contributed enormously to the rise of public debt in Pakistan (See Figure 16). 37

Pakistan is one of the prolonged users of the IMF resources. Barring four years (2004-2008), Pakistan has remained under the IMF Program since 1988 and has been implementing the 1980s stabilization program. The core policy instruments of the IMF Program have been the tight monetary policy meaning raising interest rate; tight fiscal policy meaning austerity and raising taxes; pursuing the so-called market the based exchange rate meaning devaluation; and raising the prices of utilities meaning increasing the prices of electricity and gas and hence making industries non- competitive. Pursuance of the IMF stabilization program for so long a period has worsened public debt situation in Pakistan. For more on this, see Khan [(2016), (2019a), (2019b), (2020a) (2020 b), (2021), and (2022)].

What are the factors that contributed to the extra-ordinary surge in external debt and liabilities and public debt? Factors that contributed to the rise in external debt and liabilities include:

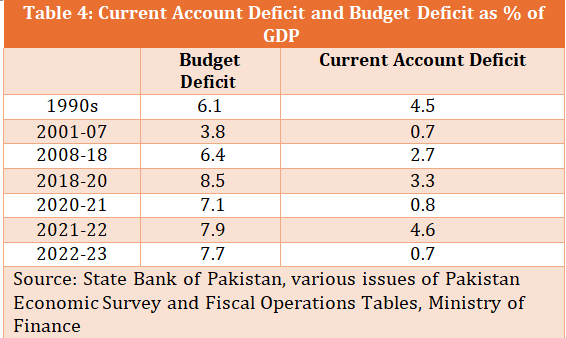

- The persistence of large fiscal and current account deficits (See Table 4),

- large amortization and interest payments, forcing the country to borrow more;

- decline in non-debt creating inflows such as foreign investment, privatization proceeds and grants assistance, forcing the country to rely more on debt creating inflows; and

- extensive borrowing at high cost for increasing foreign exchange reserves as part of the conditionalities of the IMF Program (Net International Reserves).

- Public debt increased primarily on account of massive devaluation and keeping interest rate at extra – ordinarily higher level for a longer period of time. Devaluation, by definition, is inflationary. Hence to quell inflation, the Central Bank was asked under the IMF Program to keep interest rate high. Devaluation increased the public debt without borrowing a single dollar; high interest rate simply increased the interest payment which emerged as a single largest budgetary expenditure and hence contributed overwhelmingly to keeping the budget deficit high (See Table 4). Higher budget deficit forced the government to borrow more from both the domestic and external sources to finance this deficit

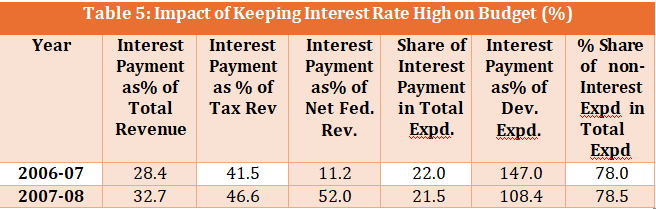

With rise in public and external debt over the years, especially during the last five years (2019-2023), Pakistan’s debt servicing liabilities has turned out to be far worse than the many LICs. Devaluation and the persistence of keeping interest rate high have created serious budgetary problems for Pakistan, especially during the last five years. Interest payment as percentage of total revenue continued to surge since 2018-19. It was 28.7 percent in 2017-18 but increased to 42.7 percent in 2018-19 and further reached to an all-time high at 59.1 percent by 2022-23 (See Table 5). In other words, almost 60 percent revenue (tax and non-tax revenue combined) was consumed by one budgetary item, that is, interest payment. 38 With respect to tax revenue only, interest payment was almost 34 percent in 2017-18 but surged to 72.8 percent by 2022-23. In other words, Pakistan consumed almost three – fourth of its tax revenue for interest payment (See Table 5). More alarmingly, interest payment alone reached over three times the development expenditure and 35.3 percent of total expenditure (See Table 5). Hence, devaluation and high-interest rate policies have seriously affected Pakistan’s economy and made Pakistan even far worse in the comity of developing countries in general and in LICs in particular as externally debt distress country.

There are 54 developing countries who spend more than 10 percent of their revenues on interest payment (See UNCTAD 2023). With 59.1 percent revenue being consumed for interest payment alone, Pakistan stands far worse than these 54 developing countries considered as debt distress countries.

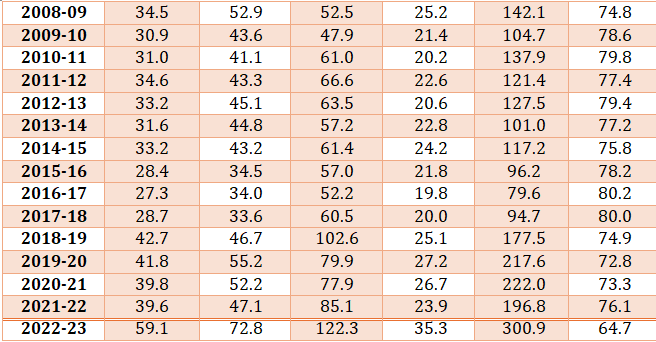

On the external debt side, Pakistan’s external debt and liabilities surged from $40.3 billion in 2006-07 to $126.1 billion in 2022-23 – an

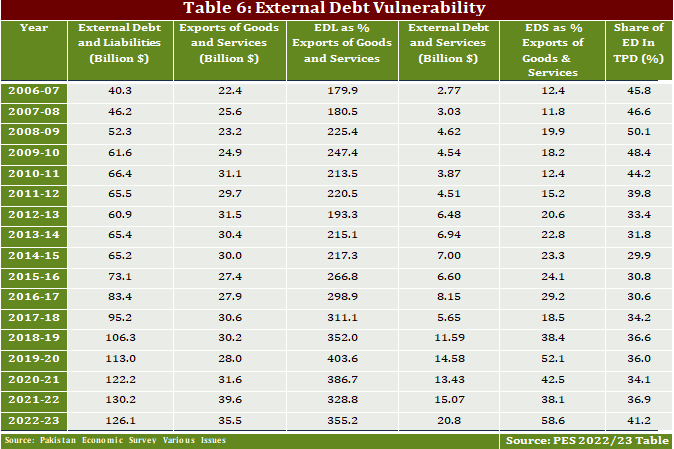

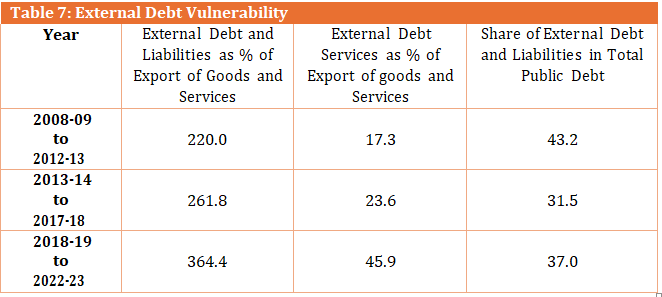

increase of three times in just 16 years have also increased the burden of debt. External debt and liabilities were 179.9 percent of exports of goods and services in 2006-07, increased to 355.2 percent by 2022-23 (See Table 6). The pace of increase accelerated with the passage of time. It was, on average, 220 percent of exports of goods and services during 2009-13, increased to 261.8 percent during 2014-18, and further increased to an average of 364.4 percent during 2019-23 (See Table 7).

Most importantly, external debt service was 12.4 percent of exports of goods and service in 2006-07, more or less in line with the average of the developing countries. It increased to 58.6 percent by 2022-23 – far worse than even the LICs (See Table 6). In other words, Pakistan spent almost 60 percent of its export proceeds of goods and services for debt servicing (both principle and intertest). The pace of debt servicing continued to rise with the passage of time. As shown in Table 7, external debt servicing, on average, was 17.3 percent of exports of goods and services during 2009-13, increased to 23.6 percent during 2014-18, and further increased to 45.9 percent during 2019-23. Once again, Pakistan’s debt burden has become far worse in the comity of developing countries in general and the LICs in particular. By looking at the burden of debt, Pakistan deserved to be considered for immediate debt relief like the other LICs.

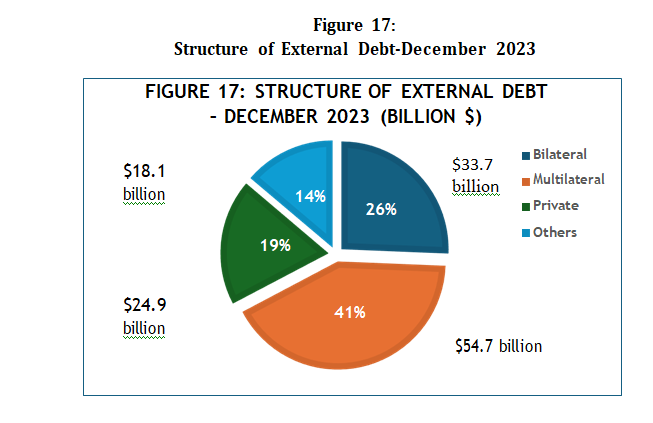

The structure or composition of Pakistan’s external debt is similar to those of low-income countries facing catastrophic debt crisis. Out of the total stock of external debt and Liabilities amounting $131.4 billion as of December 2023, bilateral debt accounts for 25.6 percent($33.7 billion), multilateral debt including the IMF debt, allocation of SDRs, SWAP etc. account for 41.6 percent, ($54.7 billion), private debt including the Eurobond, Sukuk (Islamic Bond), Commercial Loans, Commercial banks, deposits etc. account for 18.9 percent ($24.9 billion) while the remaining 13.7 percent ($18.1 billion) are other debts (See Figure 17). Hence, multilateral and private creditors together account for $79.6 billion or 60.5 percent of the total external debt and liabilities of Pakistan. Concentrating, therefore, only on bilateral debt accounting for 26 percent of external debt will not solve the problems of Pakistan including the LICs. In the G-20 Framework, the debts of multilaterals and private Creditors will have to be included for a meaningful debt relief.

Chapter VI: G-20 Debt Relief

“Debt can turn a free, happy person into a bitter human

being”

Michael Mihalik

The LICs were already facing high and unsustainable levels of debt even before the onset of the Covid-19. Over indebtedness in these countries was one of the main concerns of the 2019 Spring Meeting of the IMF-World. COVID-19 Pandemic further compounded their indebtedness and multiplied their difficulties. An IMF study, published in February 2020, well documented the over indebtedness of the LICs. According to the study, half of the LICs, that is, 36 out of 76 countries, were at high risk of debt distress or were already in debt distress conditions. 39 Sovereign debt downgrades had soared in 2020 by the major international credit rating agencies – highest level in 40 years. Argentina, Ecuador, Lebanon, Surinam and Zambia had already defaulted on their external debt payment and were at various stages of their debt restructuring process.

The Covid-19 dealt a major blow to the over 100 trillion-dollar world economy by totally devastating it with a speed which was never experienced in nearly a Century. The Covid-19 severely damaged the economies of the rich and poor countries alike, more so of the LICs. It not only knocked down their economies but greatly hampered their

39 IMF (2020), “The Evolution of Public Debt Vulnerabilities in Low-Income Countries”, Policy Paper No. 2020/003 Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund, February 10. debt repayment capacity. It is in this background that the multilateral institutions like the World Bank and the IMF along with the G-20 Countries moved forward with greater pace to assist the low-income Countries by alleviating their immediate liquidity needs to enable them to meet Covid-19 related expenditures. At the request of the leadership of the two Institutions (WB, IMF) the G-20 countries announced in Mid-April 2020 a debt payment freeze for 73 IDA eligible countries (mostly from Africa) including Pakistan. Under the Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI), the debt service payment to the official bilateral (both principal and interest) of the 73 eligible countries were suspended for the period May 1 to December 31, 2020 but was later extended up to December 2021. The purpose of debt stands still arrangement was to help debtor countries free up resources to respond to the COVID-19 related challenges. The G-20 also asked the Private Creditors (bond holders, private banks etc.) to participate in this Initiative on Voluntary Basis on comparable terms. Only one private creditor participated in this Initiative on the request of the G-20. The International Institute of Finance (IIF) led this discussion in the DSSI on behalf of the private creditors. The IIF is a global association for the financial industry that has historically served the London Club, an informal committee of commercial creditors that seeks to build consensus for restructuring syndicated loans to sovereigns. From May 1, 2020 to December 2021, the DSSI suspended $12.9 billion in debt

service payment (both Principal and interest) owed by the beneficiary countries to their official bilateral creditors. 40 This Initiative received lukewarm response from the eligible countries as only 43 out of 73 countries applied and succeeded in deferring $5.7 billion in debt service payments. The fact that this Initiative only temporarily suspended bilateral debt repayments with little or no participation from the private creditors, it made the Initiative ineffective. 41 Why the DSSI received a lukewarm response? Firstly, the structure of the debt of African eligible countries was such that only $81 billion (20%) of the total of $405 billion were owed to official bilateral creditors. However, 32% or $132 billion were owed to private creditors and 35% or $144 billion were owed to multilateral institutions. 42 Both private and multilateral institutions were excluded from this Initiative. Hence, it did not interest the eligible countries. Secondly, this Initiative barred the eligible countries to raise resources from the international debt capital market. Furthermore, the rating agencies had clearly warned that if the eligible countries insist on debt payment freeze of the private creditors, this would be treated as sovereign default and hence would attract further down grade in their

credit ratings. Thirdly, this Initiative was viewed by the eligible countries as purely temporary and will not solve their debt problem. Once the debt suspension initiative expires, the beneficial countries will have to pay back the deferred principal and interest. This deferral was Net Present Value (NPV) neutral and hence not reducing the total payments of the debtor countries. Fourthly, there was a condition in this Initiative that the countries seeking debt relief must be either already in an IMF Program or will be negotiating for a program with the IMF. Many LICs do not want to be in an IMF Program and be implementing four decades old Stabilization Program. 43

Because of the lukewarm response, the G-20 countries prepared and adopted a Common Framework in November 2021 to address insolvency and protracted liquidity problems of the LICs eligible for support under the DSSI. It provided a mechanism for debt relief on a case-by-case basis. This Framework, once again concentrated on official bilateral creditors only and also faced multiple significant operational challenges in implementing the framework. Firstly, the length of the restructuring process was considered too long, there was uncertainty regarding timelines as to when this process will be completed, combined with the lack of debt relief in the interim period, were found to be the major hindrance towards participation in the 43 More on the critical evaluation on G-20’s DSSI, See Kring, William (2021), “The Failures of the G-20’s Debt Service Suspension Initiative”, East Asia Forum, September 7 (http://eastasiaforum.org/2021/09/07); Albinet, Charles (2022)”, Looking Back at DSSI. A Perfectible Mechanism”, Finance for Development Lab Paris School of Economics, Paris, May 4, (http://findevlab.org/looking -back-at-dssi-a- tool-with-limited-effects/).

Framework. 44 Of the four African Countries – Chad, Ethiopia, Zambia and Ghana – that have applied for debt standstill under the DSSI, only Zambia has completed the process enabling it to benefit from the facility in 2023. Secondly, there was a stigma attached to the countries facing debt distress and engaging in debt restructuring negotiations. Thirdly, debt payment obligations were not halted during negotiation hence, the countries who applied for debt relief, continued to service their debts. The longer the delay in resolution of debt relief, the more pain for these countries. Fourthly, the countries engaging in the framework faced negative repercussions for sovereign credit downgrades. Fifthly, this framework lacked mechanism for coordination between creditors and debtors, particularly with respect to private creditors. Although the IIF was negotiating with private creditors for debt relief on comparable terms, there was no clear guidelines. For example, it was not clear that the eligibility will not be extended beyond the current list of countries. Furthermore, negotiating with hundreds of investors in bond market was complex and time consuming.

Notwithstanding the limitations or weaknesses in G-20 debt relief initiative, this was indeed an excellent first step in the right direction. It did provide temporary relief to some of the poorest 44 Pazarbasioglue (2024) claimed that the process of sovereign debt relief was improving. However, no significant improvement was found on the ground. See Pazarbasioglue, Ceyla (2024), “Sovereign Debt Restructuring Process Is Improving Amid Cooperation and Reform”, IMF BLOG, June 26

(http://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2024/06/24/sovereign-debt- restructuring -process-is-improving-amid-cooperation-and-reform). countries, enhanced their fiscal space and enabled them to address acute social, medical and economic challenges caused by the Covid-19. The Pandemic has caused economic devastation to many LICs along with Climate Change related disaster. The LICs face today the risk of catastrophic sovereign debt crisis with a possibility of disorderly debt defaults. A wave of sovereign defaults could be catastrophic for these countries as well as it will be a serious threat to the financial stability of advanced economies. The last time a large number of countries were at risk of default was during the Latin American debt crisis of the 1980s where a large American bank exposures to these countries triggered financial stability concern in the United States.

No meaningful debt relief can be provided to the LICs without the participation of all the three creditors, namely, the official bilateral, the multilaterals and private creditors. If international community do not provide generous support at this junction of economic history, there is a danger that the developing countries as a whole may see a protracted debt crisis. It does not make sense that the debt relief provided by the official bilateral creditors are siphoned off by multilaterals and private creditors. All the stakeholders, have to share the burden of debt relief. The matter is urgent. Many developing countries in general and the LICs in particular are facing a dark reality in choosing between debt payment and spending money on their people. There are many countries who are spending far more on debt service payments than on education and health. Pakistan is a country which is spending almost 60 percent of its revenue on debt service payments and 60 percent of exports of goods and services on external debt payments. This is nothing but sure recipe for disaster.

Chapter VII: Comprehensive Debt Relief Framework

“There are three kinds of people: the haves, the have-nots, and the have-not-paid-for-what-they- haves”.

Earl Wilson

The debt relief initiative, as mentioned earlier, was indeed an excellent first step in the right direction. However, it received lukewarm response from the DSSI eligible countries for a variety of reasons already discussed above. One of the critical drawbacks of this initiative was that it restricted to bilateral creditors (Paris and non- Paris Club members) only which accounted for, on average, around 20 percent of the external debt of the eligible countries. In other words, overwhelming external debt remained out of the purview of the Initiative. Private creditors were simply asked to participate voluntarily. The current initiative will not serve the purpose of providing debt relief to the debt ridden LICs.

In this section we propose a debt relief framework where all the stakeholders will have to play their part of the roles. Under the proposed Framework, all the three creditors, that is, bilateral, multilaterals and private creditors will have to contribute to the debt relief initiative. The author is fully aware of the fact that the multilateral financial institutions like the IMF, World Bank and the Asian Development Bank are known as “Preferred Creditors” and that their debts are neither forgiven, suspended nor restructured in normal times. But are we living in a normal time? When the LICs are spending

bulk of their revenues and export proceeds on debt repayment and depriving their people of basic needs (health, education, skills developments) are these 3.0 billion people living in normal time? The answer is that these countries are living through a difficult and challenging time. The LICs including Pakistan are facing catastrophic debt crisis. This is certainly not a normal time for them. The multilateral institutions and the private creditors must realize the severity of the ongoing debt crisis. Hence, everyone will have to contribute to this comprehensive framework. How can this be done? How can each creditor contribute to this Framework?

There are three Creditors – bilateral, multilaterals and private. Let me begin with bilateral creditors first. How bilateral creditors can provide meaningful debt relief to DSSI eligible countries?

Bilateral Creditors

Bilateral debt accounts for roughly 20 percent of external debt of the LICs. Bilateral creditors may take the following initiative:

- These bilaterals can suspend their debt repayment for ten years. Both principal and interest payment can be suspended for ten

- Bilateral creditors may also consider Debt Swap Arrangements under this Framework. Debt swap may take the following shape:

- Debt for Education Swap

- Debt for Health Swap

- Debt for SDGs Spending Swap

- Debt for Environment/Climate Change Swap

- Debt for Poverty Alleviation Expenditure Swap

- Debt for Green Swap

Bilateral creditors can enter into swap arrangements with eligible debt ridden LICs. They can select one/two or more initiatives depending upon the amount of principal and interest due. Bilateral must ensure that the amounts are sufficient for a meaningful swap arrangement. This will be a great help for the LICs because instead of repaying principal and interest in foreign currency, these monies will be used for budgetary support to undertake education, health, climate change related projects. Pakistan did enter into the debt swap arrangements with several countries in 2003 and 2004 for social sector development. The amount which was due for repayment to these countries in foreign currency were converted in Pakistani rupee. These rupees were used for agreed education, health and poverty alleviation programs in the budget. It served two purposes: first, that Pakistan did not repay these principals and interest in foreign currency, thereby relieving pressures on foreign currency reserves. Secondly, these monies were used in budget for social sector development programs, thereby reducing pressures on budget. The bilateral creditors can undertake these debt swap arrangements with eligible LICs under the proposed framework.

Multilateral Creditors

More than one-half of the LIC’s external debts are owed to multilateral institutions including the IMF and World Bank. Let the debt repayment (both principal and interest) of multilateral lending institutions (IMF, WB, ADB etc.) be suspended for ten years. This will give enough breathing space to eligible LICs including Pakistan to fix their economies and bring their debt situation at sustainable levels. It may be noted that we have not proposed debt forgiveness or debt cancelation of the multilateral debt because of their status of “preferred creditors”. What is being proposed here is simply the suspension of debt-repayment of both principal and interest for ten years. This will release plenty of resources from debt servicing to finance critical imports, finance critical spending on human capital development and infrastructure build-up. If required, the LICs may continue to borrow from the multilateral institutions, however, the borrowing requirements will be reduced significantly as these countries will not be repaying debt for ten years. The debt burden of these countries will continue to improve with the passage of time.

Private Creditors

The most difficult and challenging part of this Framework is to convince the private creditors to contribute their shares in this Initiative. once again, we are not providing debt cancellation or debt forgiveness. Rather, we are only proposing to extend the life of the bond repayments. For example, the eligible LICs including Pakistan have floated a $1.0 billion sovereign bond in the international debt capital market for a tenure of 5 years. The repayment schedule is worked out in such a way that the principal amount ($1.0 billion) and the interest are to be paid back to bond holders in 5 years’ time. What is proposed here is that this repayment schedule be extended to ten years instead of 5 years. This would reduce the debt repayment burden to one-half. It will have two benefits. Firstly, the debt repayment burden of the eligible LICs will be reduced to one-half and secondly, the bond holders will continue to receive their payments – not in 5 but in 10 years. There is no debt write off or debt forgiveness or debt cancellation in this Framework. Bond holders will continue to receive their debt repayments. Both the debtor countries and bond holders (private Creditors) are better off. This will be a great help to the eligible countries in bringing their debt situation at sustainable level.

Chapter VIII: How can this Framework be Implemented?

“Creditors have better memories than debtors”.

Benjamin Franklin

The most important challenge is that how can this framework be implemented from the G-20 platform. First and foremost is that blanket relief will not work; since the structure of the economies of the LICs including Pakistan may not be the same, therefore, a case-by-case approach will be needed to address the challenges of the poorest and low-income countries. Who will undertake this case-by-case approach? Let the G-20 hands over this responsibility to the IMF, WB and the Institute of International Finance (IIF for private Creditors) for dealing with individual country in their respective areas. These three Institutions will work in tandem with the country experts nominated by their respective country.

One thing is absolutely clear that a “one shoe fit for all” policy, as pursued by the Bretton woods Institutions in general and the IMF in particular since the 1980s will not work. The policy instruments like tight monetary policy (raising interest rate), tight fiscal policy (austerity), currency devaluation in the name of market-based exchange rate, and raising utility prices (gas, electricity) have lost it charms after the series of debt crisis in recent past, most important among them are the Latin American debt crisis, Greek debt crisis, Sri Lanka debt crisis and Pakistan’s debt crisis. The above-mentioned four policies commonly known as Washington Consensus or New Liberal

Economic Order have harmed the economies much more than they have benefited them. The outcomes of these policies have been slowing economic growth, rising unemployment and poverty, and drowning the country into debt. It is precisely the reason that why many eligible LICs did not apply for the debt relief under the DSSI because they had to go through four decades old IMF Program. These countries knew that if they go to the IMF Program to get debt relief from the G-20 Framework; instead of getting debt relief their countries would be drowned in debt.

Under the proposed debt relief framework, these three Institutions (IMF, WB, and IIF) will work closely with country experts nominated by the respective governments. These Institutions would ensure that the debt relief provided by the bilateral, multilaterals and private creditors are utilized judiciously, transparently and effectively in strengthening the economies of the LICs as well as the amount so saved by postponing the debt repayment are used for education, health, and other social sector development. Let the country experts prepare their own homegrown policies and agenda of reforms and discuss them with the representatives of these three Institutions (IMF, WB, IIF). They may suggest changes, if required, in policies and reforms but they will not force them or coerce them to pursue the neoliberal policies (the four policies mentioned above). These three Institutions will monitor the progress and report to the G-20 in its Annual Summit. The purpose of this exercise is to provide debt relief to the LICs, facilitate them, assist them in implementation of the debtrelief, and ensure that the money so saved from debt servicing is utilized for strengthening their economies and improving the lives of the people of the LICs.

The low-income countries are facing catastrophic debt crisis. Some 3.0 billion people are being affected because of their debt burden. Several attempts have been made in the past, especially from the platform of the G-20 but the results thus far have not been up to the mark. The debt relief framework presented here is comprehensive and may provide the desired relief to the LICs provided this Initiative be seen beyond the lens of the global geopolitical development or beyond the lens of the block politics. We have to see this purely from the humanitarian perspective, that is, how to improve the living standards of the billions of people in the LICs. Furthermore, it is in the interest of the advanced economies themselves to provide immediate debt relief to the LICs. Any disorderly debt default will have serious cascading effects on the economies of the advanced countries as well as on the global banking and financial sectors.

Chapter IX: Conclusions

“Debt an ingenious substitute for the chain and whip of the slavedriver”.

Ambrose Bierce

The global economy is passing through one of the most difficult and challenging times in its recent history. Higher inflation, persistence of higher interest rates, slowing Chinese economy, global fragmentation in trade and investment and climate change are some of the serious challenges the world is confronting today. All these challenges combined can be described as ‘polycrisis’ and contributed immensely in drawing the developing countries in general and the LICs in particular into debt with little capacity to service their debts. Hence, the list of debt distress countries is growing with a strong possibility of disorderly debt default in the LICs.

The debt crisis of developing countries in general and the LICs in particular are aggravating at a time when the world economy is rapidly fragmenting as a result of the changing geopolitical and geoeconomic environment. The world appears to have been divided in three blocs – a US leaning bloc; a China leaning bloc; and a non-aligned bloc. However, the speed at which the fragmentation in global economy is taking place, the third bloc (non-aligned bloc) would vanish soon with only the two blocs remaining in the field. Amid this global development, the debt situation in developing countries, particularly in the LICs are deteriorating. Many of these countries are likely to experience disorderly debt defaults, if no comprehensive debt relief are provided to them urgently. The advanced economies must see these challenges beyond the lenses of the bloc politics. There are humanitarian issues along with economic ones. Every effort must be made to prevent disorderly debt defaults and provide them urgent debt relief. These countries have very little time left. Their earnings are diminishing because of the global economic challenges; however, whatever they are earning, bulk of these are being used to service their debts at the cost of the welfare of 3.0 billion people living in these countries. These countries are spending much more on debt payments than spending on education, health, safe drinking water, sanitation and climate change. Among these countries, Pakistan is spending almost 60 percent of its revenue and 60 percent of its exports of goods and services on debt servicing against the global benchmark of 30 percent.

The LICs were already facing high and unsustainable debt, the COVID-19 dealt a major blow to the deteriorating debt situation of these countries. The International Financial Institutions, particularly the IMF and the World Bank along with G-20 countries moved forward with greater pace to assist the LICs by alleviating their immediate liquidity needs to meet COVID-19 related expenditures. A Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) was launched for the 73 IDA eligible countries including Pakistan to provide them immediate debt relief. This Initiative was excellent first effort in the right direction. However, it received lukewarm response from the eligible countries because it concentrated only on bilateral debt which accounted for nearly 20

percent of their outstanding debt. Private creditors were asked to voluntarily participate in this Initiative on comparable term. In other words, bulk (80%) of their debts remained out of the purview of this Initiative. Furthermore, the process of the debt relief was highly cumbersome as well as these countries were asked to negotiate with the IMF for a new program. Many LICs do not want to be in the IMF Program because of its painful conditionalities. Hence, a lukewarm response was given to the Initiative by these eligible countries.

The main thesis of the report is that no meaningful debt relief can be provided to the eligible countries without the participation of all the stakeholders or creditors, that is, bilateral, multilaterals and private creditors because of the nature and composition of the debt of these countries. Hence, a comprehensive debt relief framework has been presented here in this report where all the three creditors will have to work in unison to provide a meaningful debt relief. This framework does not recommend debt forgiveness or debt cancelation but only recommends debt suspension.

Bilateral Creditors may suspend their debt repayment for ten years. Besides, it is proposed that they may enter into various debt swap arrangements with the eligible countries. This will be a great help for the eligible LICs because instead of repaying principal and interest in foreign currency, they will be using these monies for budgetary purposes to spend on education health, climate change and improving other social indicators.

Multilateral Creditors accounting for more than one-half of their external debt may also suspend their debt repayments for ten years. This will provide enough breathing space to eligible LICs including Pakistan to fix their economies and bring their debt situation at sustainable levels. This will release substantial resources from debt servicing to finance critical imports, finance critical spending on human capital development and infrastructure. These countries will not be borrowing to finance these activities, hence will slow down the pace of debt accumulation.

Private Creditors are simply asked to extend the maturity of the sovereign bonds. For example, if the eligible LICs including Pakistan have floated a $1.0 billion sovereign bond with 5 years maturity, the repayment schedule is prepared in such a way that the principal amount and the interest rate are to be paid back to the bond holders in 5 years. It is proposed here that the repayment schedule be extended to ten years instead of 5 years. This would reduce the debt repayment burden by one-half for the LICs and bond holders will continue to receive their payments – not in 5 years but in 10 years. This will help the eligible countries to bring their debt situation at sustainable level.

How can this proposed framework be implemented from the platform of the G-20? First of all, there will not be a blanket relief for the eligible countries. This relief framework will be monitored by the G-20. Secondly, a case-by-case approach will be needed in this case because the structure of the economies of these LICs including Pakistan are different. Hence, one shoe fit for all policy will not work. Who will undertake the case-by-case approach? The G-20 can handover this responsibility to the three institutions, namely the IMF, the World Bank and the International Institute of Finance (IIF) for private creditors only. These three Institutions will work in tandem with the respective experts from the eligible countries nominated by these countries themselves.

It has to be noted that the IMF stabilization program, particularly its four standard policies, that is, tight monetary policy (raising interest rate), tight fiscal policy (austerity), the so-called market-based exchange rate (currency devaluation), and raising utility prices (gas and electricity) must be avoided at all costs. Such policies have drowned these eligible countries including Pakistan in debt. Hence, these policies will be counterproductive for the comprehensive debt relief framework. It is precisely the reason as to why these eligible countries did not take serious interest in the DSSI because they had to go to the IMF for a Program and implement the above-mentioned four policies. Let the country expert prepare their home-grown policies and agenda of reform and shared with the representatives of these three Institutions. They may suggest changes, if required, in policies and reform but not force or coerce them to pursue the above-mentioned four policies. Leave the policies and reform with the country experts because they know their economies well. These three Institutions will monitor the progress and report to the G-20 during its Annual Summit.

The LICs are facing catastrophic debt crisis. It is affecting the lives of over 3.0 billion poor people. They need urgent debt relief from the platform of the G-20. Although, some efforts were made after the pandemic to provided debt relief to the IDA eligible countries, it did not attract much attention from the perspective of the beneficiaries. The debt relief framework presented here is comprehensive and include bilateral, multilaterals and private creditors. This framework, if implemented from the platform of the G-20, is expected to provide meaningful debt relief provided that this Initiative be seen beyond the lens of the geopolitical development or beyond the lens of the bloc politics. It is proposed here as a humanitarian issue because it involves the well-being of over 3.0 billion people.

Dr. Ashfaque Hasan Khan is currently the Director General, NUST Institute of Policy Studies (NIPS), Islamabad, a university-based Think Tank. He has been the Principal & Dean of the two prestigious Schools of NUST, namely the NUST Business School and the School of Social Sciences and Humanities for fourteen and a half years. He has been appointed as Member of the Advisory Council of the Asian Development Bank Institute (ADBI), Tokyo by the President of the Asian Development Bank, Manila for the period (2022-2024). The Chairman of the International Finance Forum (IFF), Beijing, a former Prime Minister of the Republic of Korea, has appointed Dr. Khan as Member of the Academic Committee of the IFF for five years (2023- 2028). He is also the Member of the Senate of the Pakistan Air War College Institute, Faisal Base Karachi. He has been a member of the Economic Advisory Council as well as the member of the Macroeconomic Advisory Council of the Prime Minister. He has also been the Member of the Senate of the National Defence University, Islamabad appointed by the President of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan. The Higher Education Commission (HEC) has appointed him as member of the Senate of the Pakistan Institute of Development Economics (PIDE), Islamabad. He has also been elected as member of the Board of Trustee of the International Islamic University, Islamabad.

He is also a member of the Board of Governor of the Foundation University, Islamabad. Dr. Khan has been the Special Secretary Finance/Director General, Debt Office and Economic Adviser, Ministry of Finance, Islamabad for eleven years (1998-2009). He has also been the Spokesperson of the Government of Pakistan on Economic Issues during the same period (1998-2009). He has been the Director and Vice Chairman of the Saudi-Pak Industrial and Agricultural Investment Company Ltd. (A joint venture of Saudi Arabia and Pakistan); and Directors of the United Bank Limited (Representing government’s shares in the Bank) and Pak-Libya Holding Company (A Joint venture of Pakistan and Libya).

Dr. Khan holds a Ph.D. degree in economics from The Johns Hopkins University in USA. He joined the Pakistan Institute of Development Economics (PIDE) in 1979 as Research Economist, where he held increasingly senior positions. He was Joint Director of the Institute before being appointed Economic Adviser of the Ministry of Finance in March 1998. In January 2003 he was appointed Director General of the Debt Office of the Ministry of Finance. He was appointed Special Secretary Finance/ Director General, Debt Office in July 2007- a position which he held until February 2009.

As a member of the high-level Debt Committee, Dr. Khan was involved in the preparation of the Debt Reduction Strategy which was later adopted by the Government. He also played an important role in setting up the Debt Office in the Ministry of Finance. Within eight years of pursuance of the same strategy the country’s public debt was reduced to one-half and Pakistan was able to prepay expensive external debt. Dr. Khan is the principal architect of the Fiscal Responsibility and Debt Limitation Act, passed by Parliament in June 2005. This Act was designed to inject financial discipline into the country. Dr. Khan has been actively involved in the floatation of Pakistan’s sovereign bonds including the Islamic bond (Sukuk) in the international debt capital market.

Dr. Khan’s experience includes visiting Lecturer at the Towson State University, Baltimore, USA and Visiting Fellow at the Kiel Institute of World Economics in Germany. He has also been the Consultant to many International Organizations/ Financial Institutions such as the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and Pacific (UN-ESCAP), the Asian and Pacific Development Centre, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, the Asian Development Bank and the World Bank. As Consultant to the Secretary General SAARC, he has the honour of preparing the Regional Study on Trade, Manufacturers and Services which served as the foundation for regional cooperation in South Asia including the establishment of the SAARC Chamber of Commerce and Industry.

Dr. Khan has the distinction of being the most widely published economist of the country. He has published 11 books and more than 185 articles in national and international journals of economic science. His papers have appeared in the most prestigious journals of economic science published by Harvard University and University of Chicago. Dr. Khan has also the distinction of being a student of a Nobel Laureate in economics, Professor Lawrence R. Klein.

He has been the editor, co-editor, and the member of the Editorial Committee of the various prestigious journals of economic science. He has been the recipient of various awards from the National Book Foundation for publishing articles in International Journals of economic science. He is also the external examiner of Ph.D. dissertation submitted to various Pakistani and foreign universities. Dr. Khan is a frequent speaker at the National Defence University, Pakistan Administrative Staff College, National Institute of Public Administration (NIPAs); the Army School of Logistics, Kuldana; Army School of Infantry, Nowshera; the Command and Staff College, Quetta; Ordinance College, Malir Cantt, Karachi; PAF Air War College, Karachi, National Command Authority and Foreign Service Academy of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

In recognition of his outstanding contribution to the field of economics and public policy the President of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan has conferred the award of Sitara-i-Imtiaz to Dr. Khan in 2005. The Economic Cooperation Organization (ECO) – a regional bloc consisting of Pakistan, Iran, Turkey, Afghanistan and six central Asian states (Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan) also conferred him the ECO Excellence Award 2010 for his outstanding contribution in the field of Economics.

Credit: Independent News Pakistan (INP)