INP-WealthPk

Moaaz Manzoor

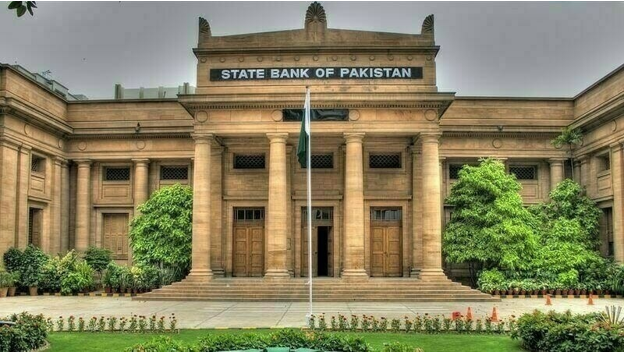

The State Bank of Pakistan’s decision to maintain the policy rate has sparked a debate on its impact, with economists divided over whether it ensures stability or stifles economic recovery amid rising external pressures and sluggish growth, reports WealthPK. While the central bank argues that inflationary pressures and external vulnerabilities necessitate caution, businesses and analysts question whether this approach is stifling economic recovery.

Speaking to WealthPK, Rao Asad, an economist at the Federation of Pakistan Chambers of Commerce & Industry (FPCCI), believes the SBP’s cautious stance is justified given the ongoing external risks. He points out that despite foreign exchange reserves recovering to $15.9 billion as of March 9, 2025, they remain well below the $22 billion peak in the third quarter of FY22.

“The external sector is once again under pressure, with the current account turning negative in January 2025 after months of surplus. The 172% decline — from a $582 million surplus in December 2024 to a $420 million deficit in January 2025 — highlights the vulnerability of Pakistan’s trade balance, which has been driven by rising imports and debt-related payments”.

Given these challenges, Asad warns that excessive rate cuts could fuel an import surge, further widening the current account deficit and depleting reserves at a time when economic buffers are crucial. Syed Ali Ehsan, Deputy Executive Director at Policy Research Institute of Market Economy (PRIME), offers a contrasting view, arguing that SBP’s policy pause is constraining growth at a time when Pakistan needs to push beyond its sluggish 2.5-3.5% GDP growth forecast for FY25.

“A few decimal points above population growth is not economic progress,” he remarks, adding that the country needs sustained expansion to make meaningful economic strides. While SBP has justified its decision by citing rising import-based activity, Ehsan believes the real issue is stagnant domestic production. “Agriculture is struggling, manufacturing is stagnant, and high energy costs, interest rates, and taxation have rendered local industries uncompetitive against imports.”

By keeping policy rates high, the SBP has also inadvertently increased the government’s debt servicing costs, reinforcing Islamabad’s reluctance to implement structural reforms. “Despite 24 months of record-tight monetary policy, the government has barely moved on long-overdue economic reforms,” Ehsan says, stressing the need for a cut in government expenditure, reduced reliance on indirect taxation, and making state-owned enterprises more efficient.

“Without such reforms, monetary policy alone cannot drive sustainable economic growth.” The SBP’s latest move signals that it has done its part in stabilising macroeconomic fundamentals under the IMF programme. However, the next phase of economic correction is in the government’s hands. Whether policymakers will seize the moment to enact genuine reforms or continue with temporary fixes remains to be seen. What is clear, however, is that Pakistan cannot afford to remain in an economic holding pattern while structural inefficiencies persist.

Credit: INP-WealthPk